Rise of the Nigerian threat group SilverTerrier

In July 2014, Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 released its first threat intelligence report on Nigerian cyber actors. This report documented the observed evolution from traditional 419-style email scams to the use of commodity malware for financial gain.

Applying advanced analytics across more than 8,400 samples resulted in the identification of over 500 domains supporting malware activity and roughly 100 unique actors or groups, which continue to be track under the code name SilverTerrier.

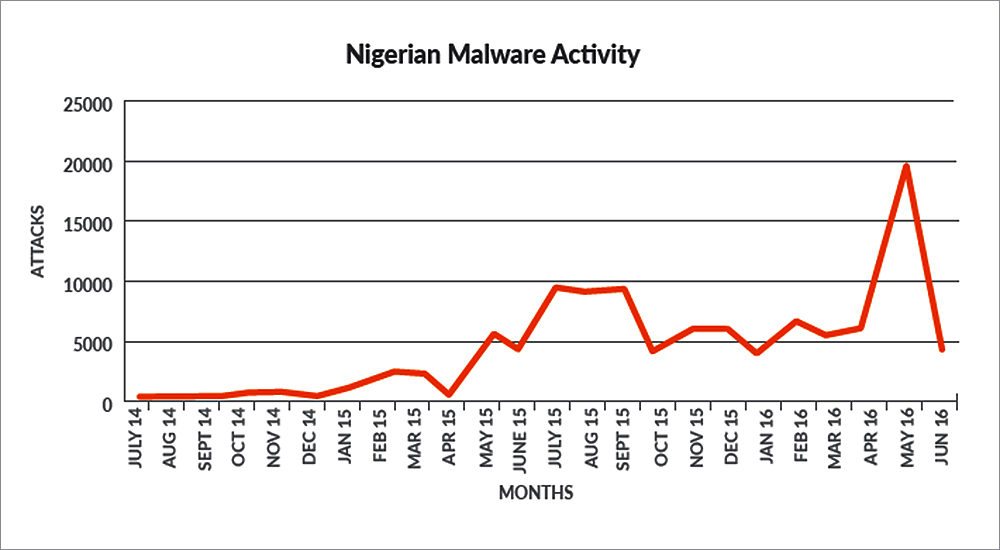

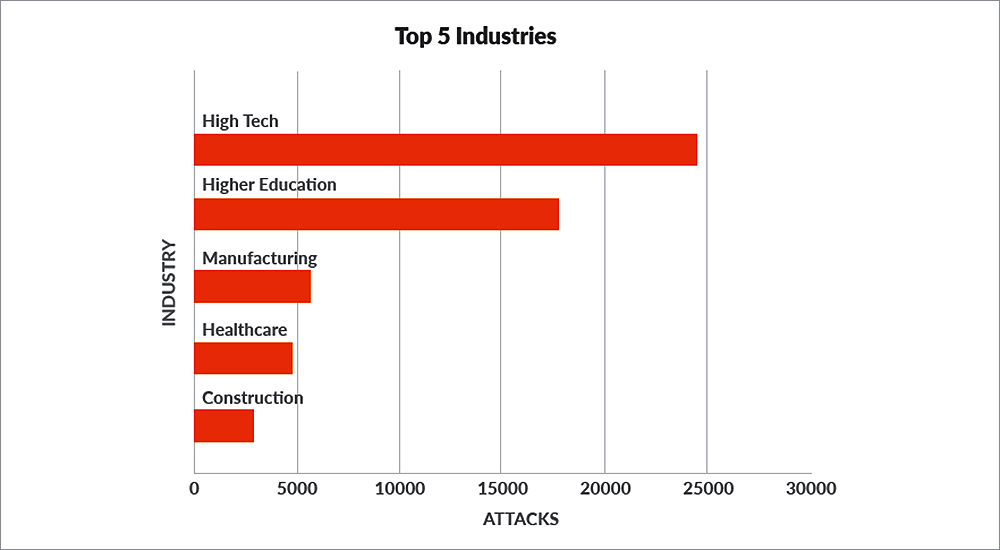

The data exhibited that the ability of these actors to distribute malware has grown steadily over the past two years to its current rate of 5,000–8,000 attacks per month. Moreover, using email as the primary means of distribution, the majority of these attacks were focused against the high technology, higher education and manufacturing industries.

While these attacks originate from actors with varying degrees of technical expertise, all of the actors continue to rely on commodity malware tools, which require minimal infrastructure to set up and can be acquired on underground forums at nominal costs.

Through analysis, it has become clear that Nigerian cyber actors have demonstrated significant growth in size, scope and capability over the past two years. They have learned how to successfully apply simple malware tools with precision in order to create substantial losses ranging from tens of thousands up to millions of dollars for victim organisations. They have broadened their scope well beyond targeting unsuspecting individuals.

In 2008, Federal Bureau of Investigation released its annual Internet Crime Report listing Nigeria as third in the world for conducting cybercriminal activity. While the country’s position on the list has fluctuated over the years, it once again claimed the number three position in last year’s report.

Since 2014, Nigerian actors have been linked to various popular malware tools, including Zeus, DarkComet and others. All of these tools have something in common: they are commodity malware tools that require minimal infrastructure to set up and can be purchased at nominal costs on underground forums. Traditionally, this fact has been used to justify assessments that suggest these actors lack the technical aptitude required for more advanced tools.

But research suggests that these tools may be chosen intentionally to support easy scalability among a distributed actor network similar to an organised crime model.

Analysing their use of the five core malware tools, the ability of SilverTerrier actors to distribute malware has grown steadily over time to its current level of 5,000–8,000 attacks per month. However, in May 2016, they demonstrated the added ability to surge distribution efforts by launching nearly 19,000 attacks in one month.

While the malware itself can be distributed at scale and in far greater numbers than observed above, the benefits of doing so are often diminished for these actors.

As a basic principle, there is generally a correlation between the amount of malware distributed and the time it takes for antivirus vendors to identify and block it. Thus, these Nigerian actors have refined their attack methods over time from sending malware in bulk across the internet to a more focused, deliberate and targeted approach. Specifically, data showed that 86% of the malware samples analysed were observed in 20 or fewer attacks against Palo Alto Networks customers.

These targets fall across all lines of industry. However, the data shows that Nigerian actors are predominately targeting organisations in high technology, higher education and manufacturing. This pattern represents a significant departure from traditional Nigerian criminal activity, which historically has been focused on individuals and petty crime, to a much more substantial threat for the international community, targeting everything from small businesses to major corporations.

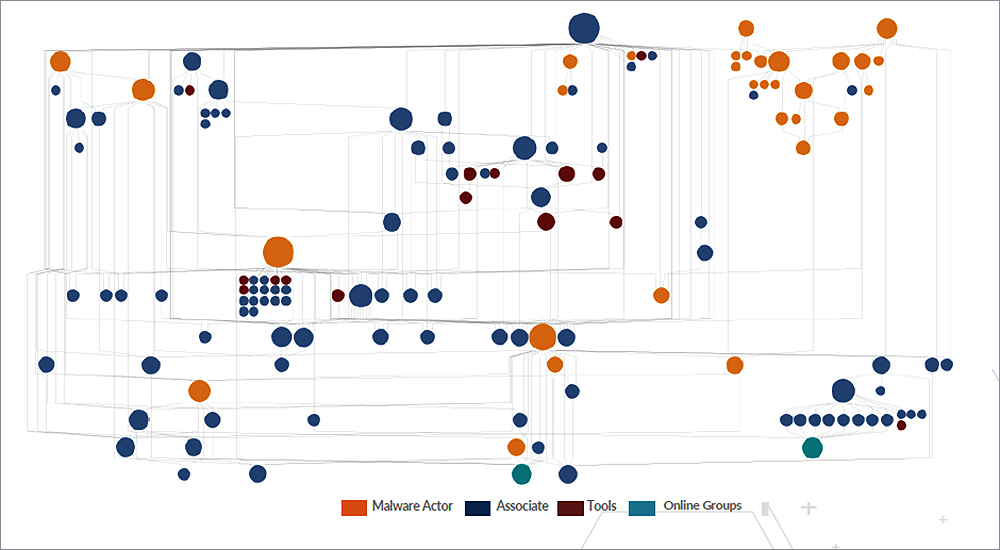

Using AutoFocus contextual threat intelligence, combined with advanced analytic practices, Unit 42 is currently tracking roughly 100 Nigerian cyber actors responsible for operating the infrastructure associated with the five identified malware families. These actors were predominately identified using domain registration details, which, in many cases, enabled Unit 42 to link these actors directly to their social media profiles.

Performing this practice on a large scale has produced tremendous insights into the size, scope, motivations and interactions of these actors.

At any point in time, many of these actors are engaged in multiple categories of scams ranging from their traditional 419 emails, to fake websites, to the most recent malware initiatives. Thus, in order to account for the range of their activities, it becomes necessary to discuss the domains that SilverTerrier actors are building to support their activities. These domains can be grouped into three generic categories: self-named, fake organisations, and impersonation of legitimate organisations.

The ability to provide accurate metrics for the victims of these attacks presents a unique challenge for cybersecurity analysts. This information is clearly valuable, as it supports the capability to quantify the level of success being achieved by Nigerian actors. However, the issue lies in distinguishing between individuals and organisations that were targets of these attacks, as compared with the organisational systems that were actually compromised by the malware. Most security vendors have ample data on which of their customers were targeted and how those attacks were launched.

The majority of the victims were located in the Middle East and Asia, with a smaller subset in Europe and North America. All of the victims ran Microsoft Windows operating systems, many of which contained traditional endpoint antivirus solutions. Additionally, several of these systems were observed to contain timecard, billing and inventory software.

The victim organisations also ranged in size from small to medium-sized businesses with both local and global footprints. However, while Nigerian actors focus their malware efforts against targets they believe to be profitable, this activity is sometimes indiscriminate and can result in significant secondary impacts to the international community.

For example, one such victim identified by Unit 42 was an organisation that serves as the intermediary between international telecom providers and their national government, in order to shape domestic policy. In cases such as these, the risks to society become an order of magnitude greater, ultimately placing these cyber actors on a different playing field from those traditionally thought of as low-level cybercriminals.

While next-generation security solutions are highly effective at identifying Nigerian cybercriminal activity, traditional antivirus solutions are far less successful. An analysis of over 8,400 malware hashes submitted to VirusTotal showed an average identification rate of only 52% across vendors. This presents challenges to businesses worldwide that rely on legacy endpoint products alone to protect their employees when traveling outside the more sophisticated protections corporate networks typically provide.

Finally, these attacks have matured. Businesses have become the primary focus of Nigerian cybercrime, and the losses have already proven to be substantial. Proof of an individual actor’s ability to steal $60 million, as well as evidence that groups using these techniques have been successful at stealing $3–6 million annually, should be considered a measure of their criminal competence.

Because of these traits, it is assessed that Nigerian actors have demonstrated a clear growth in size, scope, complexity and capability over the past two years, and as a direct result, they should now be regarded as a formidable threat to businesses worldwide.